Kilimanjaro News Network

The Voice of Africa

UMOJA

NA MAENDELEO

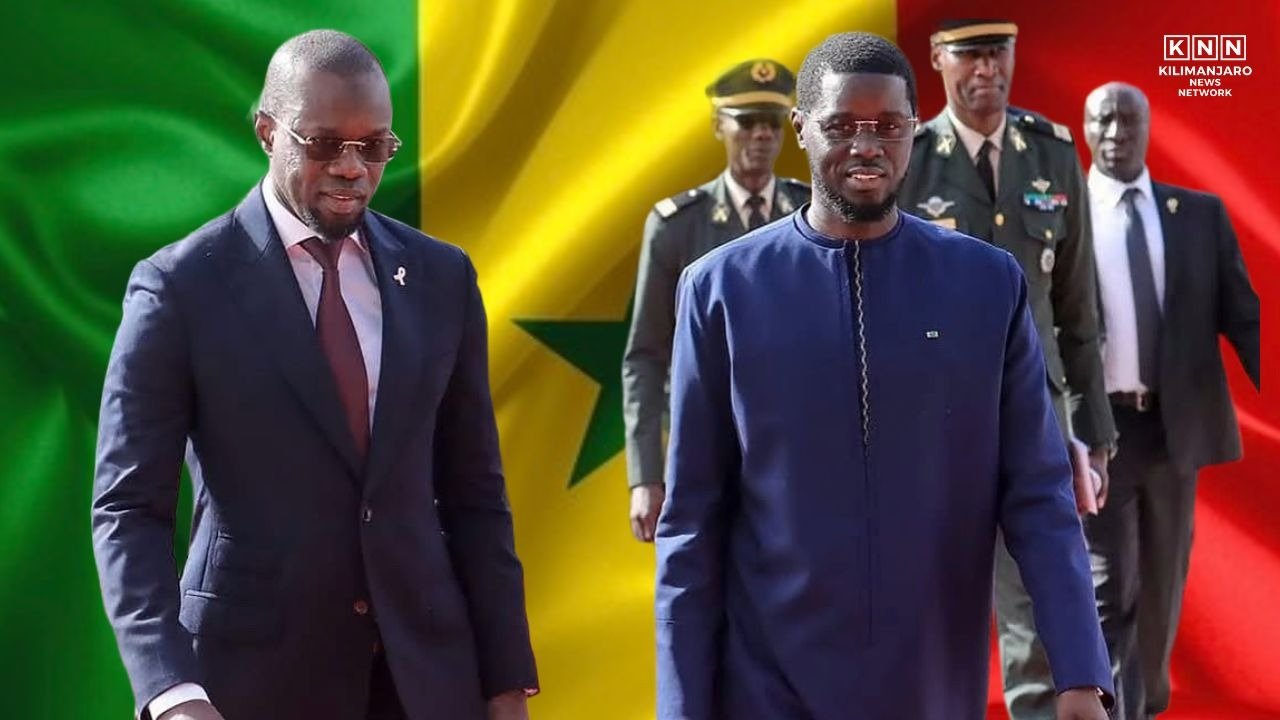

DAKAR-SENEGAL: You can almost feel the tension in Dakar these days, like a wire pulled tight between two visions of the same dream. What’s unfolding in Senegal isn’t just another political spat, or the all-too-familiar story of a reformist president at odds with his firebrand prime minister. It’s something more elemental: a confrontation with the very machinery that has shaped Africa’s post-colonial trajectory for more than half a century.

The Faye–Sonko split is less a disagreement than a diagnostic, a kind of living, breathing autopsy of what sovereignty actually costs when the abstractions give way to the numbers, the treaties, the debt calendars, the currency pegs. And in this autopsy, the instruments are as revealing as the wound: the CFA franc, the IMF, the long-promised but never-delivered Eco.

For a moment, back in March, when Bassirou Diomaye Faye rode a tidal wave of popular frustration into the presidency, there was a sense that Senegal had broken free of everything that defined the post-independence era: the deference to Paris, the monetary architecture built elsewhere, the quiet dominance of multilateral institutions with their velvet gloves and iron expectations. People called it an “Ablaque” a peeling away of the old skin. You could hear the word whispered on street corners, in taxis, in university cafeterias. A new start; finally.

But revolutions, once they enter the phase of budgets and balance sheets, rarely stay pristine for long.

The Currency Question: A Chain or a Safety Net?

It’s almost impossible to overstate the symbolic weight of the CFA franc in West Africa. For Ousmane Sonko and his movement, it is not just a currency, it is the master key to the entire colonial hangover. The peg to the euro, the guarantees held in Paris, the monetary policy tethered to a foreign centre of gravity: these aren’t technicalities; they are the architecture of dependency.

The promise was clear during the campaign: the CFA would go.

Now, six months later, President Faye finds himself charting a slower path, talking not of a dramatic exit but of migrating toward the Eco, the long-imagined regional currency that has spent two decades being discussed, postponed, relaunched, and diluted. The Eco could, in theory, break the colonial lineage. Or it could simply reproduce the CFA’s logics under an African logo.

For Sonko’s base, the hesitation smells like betrayal. A revolution with a timetable is already compromising. A revolution that consults with its former overseers is something worse.

And yet, the hard data refuses to budge. Senegal’s economy is deeply, dangerously, entangled with the Eurozone. A sudden rupture would be like yanking the power cable out of a running machine: you wouldn’t just hear a pop; the whole system could fry. Imports would spike in price, capital would flee, inflation would roar. The very people calling for liberation would bear the heaviest weight of it.

That is Faye’s dilemma: the chains are real, but so is gravity.

The IMF: A Lifeline with a Noose Attached

If the currency question is emotional, the IMF question is existential.

Senegal is carrying a public debt above 75% of GDP, a figure inherited from years of infrastructure expansion fuelled by external borrowing. Salaries, subsidies, and critical state functions depend on predictable inflows.

Sonko wants nothing to do with the IMF. He speaks of its programs as a waiting room for countries destined to never walk again. His stance is uncompromising: African nations cannot reclaim their destiny while outsourcing macroeconomic policy to Washington. Any new program, in his eyes, would be the first crack in the revolutionary façade.

Faye’s ministers, meanwhile, are negotiating quietly but urgently for a limited arrangement “budget support,” they call it, with an emphasis on minimising conditionalities. Their argument is cold but grounded: a sovereign default would do more damage to the revolution than any temporary reliance on outside financing. A political project without liquidity does not survive; it evaporates.

This is the old debate dressed in new clothes: gradualism versus rupture, patience versus purification. African history is cluttered with examples of countries that bought time today by mortgaging tomorrow.

Sonko knows that. Faye knows that. The difference is simply which risk each man fears most.

Audits as Liberation: A Technocrat’s Gambit

There is an elegance, almost a fragility, to the strategy Faye has chosen in the extractive sector. Rather than storming in with nationalizations and unilateral terminations, he has armed the state with auditors, lawyers, and forensic accountants. Every contract signed during the oil and gas boom is being pulled apart stitch by stitch.

The idea is simple: use the fine print to reclaim sovereignty without triggering an investor stampede.

To his critics, this looks like threading a needle while the house burns. International arbitration courts were never built for African reclamation; they were built to preserve foreign stakes under the guise of neutrality. An audit, they argue, is a negotiation within the rules of a game designed to ensure Africa never wins.

But Faye is betting on something subtler that the world has changed just enough, and Senegal’s positioning is strong enough, to redefine the terms of engagement without breaking the table.

It’s a delicate calculation. Maybe too delicate.

The Brutal Math of Liberation

This is what it comes down to: a president trying to land a complex aircraft whose wings were designed in Paris, whose engine is maintained by the IMF, whose fuel comes from creditors, and whose passengers are demanding a dive into uncharted air. And beside him, a prime minister insisting that the only way to fly is to rip the plane apart mid-air and build a new one from the pieces.

History is not kind to either strategy.

The first generation of African leaders: Senghor, Houphouët-Boigny, Nyéréré, and all those who attempted careful, “responsible” transitions, were told to be patient. Gradualism became the ideology that ate a continent. Sonko’s movement knows this. It is why his voice resonates so sharply.

But so does the memory of states that chased rupture and found themselves cornered, economically isolated, politically vulnerable, or quietly coerced back into the same patterns they sought to escape.

Senegal, without intending to, has become the continent’s most revealing stress test. The question is not simply whether Faye or Sonko is right. It’s whether any African state can achieve real sovereignty while operating in a global system calibrated to penalize independence.

Everyone, from Bamako’s junta to Pretoria’s strategists, has their eyes on Dakar. If Senegal finds a third path, a way to break from the past without triggering economic freefall, it will redraw the map of African autonomy. If it fails, the lesson will be equally strong: liberation cannot be sequenced; it must be seized whole.

One way or another, Senegal is about to show Africa and the world, whether gradual emancipation is possible, or whether the only path out of a trap is to stop negotiating with it.